As a framework to support teaching and learning, Bloom’s taxonomy is the most widely used and enduring tool through which to think about students’ learning. Originally created by the American educational psychologist, Benjamin Bloom in 1956, Bloom’s taxonomy provides a hierarchical ordering of cognitive skills and is used worldwide to help inform successful teaching practice.

The creation of Bloom’s taxonomy after the Second World War reflects the increasing importance of formal education to industrialised society. In a world in which formal education began to play a greater role than ever before, Bloom’s taxonomy quickly became popular as a way to formalise teaching and learning practices, help write exams and develop curricula.

The fact that Bloom’s taxonomy can be applied to any (cognitive) content intended for students to learn, is what makes this framework so powerful. It can be seen, to a greater or lesser extent, in all mark schemes and assessment objectives provided by all examining bodies in almost any curriculum subject. For teachers, Bloom’s taxonomy is a practical tool to use, providing a framework in which to plan challenging lessons that help to ensure students’ progress is maximised – a fundamental tenet of successful teaching. Among its many uses, Bloom’s taxonomy provides an excellent foundation for lessons, as it can be used as a framework in which to deliver appropriate activities, assessment, questioning, objectives and outcomes.

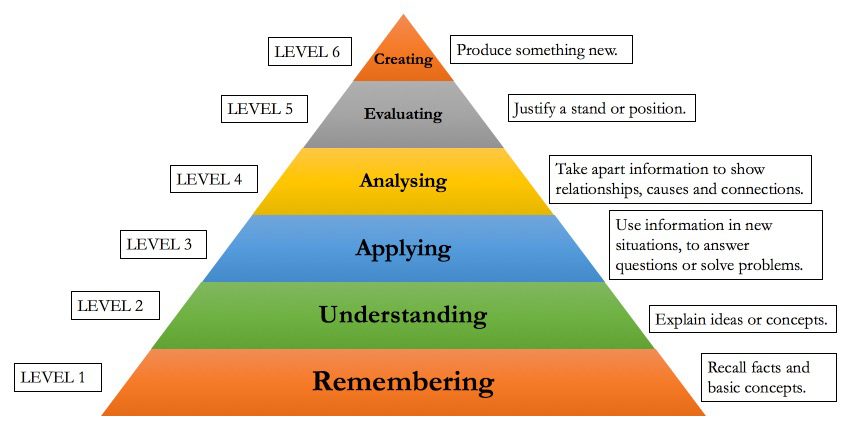

It is worth taking the time therefore, to become familiar with the categories of the taxonomy, their order and their meaning. I illustrate Bloom’s taxonomy[1] here, including some examples of keywords associated with each level (shown in italics).

Level 1, Remembering, is the most basic, requiring the least amount of cognitive rigour. This is about students recalling key information, for example, the meaning of a word.

|

Arrange |

Define | Describe | List | Match | Name | Order | Recall |

Reproduce |

Level 2, Understanding, is to do with students demonstrating an understanding of the facts remembered. At this level, the student who recalls the definition of a word, for example, would also be able to show understanding of the word by using it in the context of different sentences.

| Classify | Discuss | Explain | Identify | Report |

Summarise |

Level 3, Applying, is concerned with how students can take their knowledge and understanding, applying it to different situations. This usually involves students answering questions or solving problems.

| Apply | Calculate | Demonstrate | Interpret | Show | Solve |

Suggest |

Level 4, Analysing, is about students being able to draw connections between ideas, thinking critically, to break down information into the sum of its parts.

|

Analyse |

Appraise | Compare | Contrast | Distinguish | Explore | Infer |

Investigate |

Level 5, Evaluating, is reached when students can make accurate assessments or judgements about different concepts. Students can make inferences, find effective solutions to problems and justify conclusions, while drawing on their knowledge and understanding.

| Argue | Assess | Critique | Defend | Evaluate | Judge |

Justify |

Level 6, Creating, is the ultimate aim of students’ learning journey. At this final level of Bloom’s taxonomy, students demonstrate what they have learnt by creating something new, either tangible or conceptual. This might include, for example, writing a report, creating a computer program, or revising a process to improve its results.

|

Compose |

Construct | Create | Devise | Generate | Organise | Plan |

Produce |

As Bloom’s taxonomy is a hierarchy of progressive processes ranging from the simple to the complex, in which it is necessary to first master those lower down the pyramid before being able to master those higher up, the framework promotes what Bloom termed ‘mastery learning’. In other words, by moving up the taxonomy, students become more knowledgeable, more skilled and develop an improved understanding of the content they are learning. Thus, by creating lesson plans and tasks, using the examples of verbs (in italics) provided, teachers can align with the different levels of the taxonomy.

By simply moving to the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy, these verbs can serve as the basis for learning objectives, questions or activities. They describe what we want students to be able to do, cognitively, with the content about which the students are learning. The higher up the pyramid of course, the more complex are the cognitive processes involved and, as such, ask students to engage in more challenging cognitive work connected to their lesson’s content. As part of successful teaching practice, it may be necessary to adjust the level of challenge based on student responses, moving down the taxonomy as needed.

A lesson could be planned about the benefits of renewable resources, the Roman empire, building a website or one of Shakespeare’s sonnets. In all these examples, Bloom’s taxonomy can be applied. An important point to consider, however, is that there can be occasions, particularly when first introducing a topic, where it is necessary to spend longer on the lower levels of the taxonomy. On such occasions, we do not seek to scale multiple levels of the taxonomy in a single lesson, instead choosing to do this over the course of a few lessons, due to the nature of the content (Gershon, 2015, pp. 103).

For example, for a series of Computing lessons that teach students how to build a webpage, the first lesson could explain to them about HTML, leading to a discussion about an example of HTML script and how it translates into a webpage (Level 1 – Remembering), before asking them to explain the purpose of different parts of the HTML script (Level 2 – Understanding). Students would move on to applying their knowledge and understanding of HTML, to begin building their own basic webpage, requiring them to solve any problems in their script (Level 3 – Applying), and then investigating additional features that could be added to their webpage (Level 4 – Analysing). As the lessons continue, students could be challenged further to critique their website, assessing its strengths and how it could be improved (Level 5 – Understanding). At the pinnacle of Bloom’s taxonomy, it would be expected for students to create something completely new or original, producing a website that fulfils a particular purpose (Level 6 – Creating).

Similarly, for a series of literacy lessons looking at John Yeats’ poem, ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’, the following tasks could be set according to each category of Bloom’s taxonomy. After reading the poem together as a class, students could be asked to recite the first stanza of this poem (Level 1 – Remembering), before being asked where Yeats would like to be, London or the Lake Isle of Innisfree (Level 2 – Understanding). Afterwards, students could move on by describing the structure of Yeats’ poem, explaining his use of rhythm and rhyme (Level 3 – Applying). In the subsequent lesson, students might be asked to analyse the mood of this poem, exploring how mood is created (Level 4 – Analysing). Later on, students could be asked to pick one of the images from the poem, evaluating its effectiveness (Level 5 – Evaluating). Finally, an appropriate activity to this finish off the topic might be to get the students to write their own poem on a similar theme (Level 6 – Creating).

Another point to make clear is that the separate processes of the taxonomy can be adapted according to the age-group and ability of students, enabling them to access the different levels of taxonomy according to the overall depth of their cognition. Level 6, Creating, for example, is obviously not going to be the same for a five-year old as it would be for a sixteen-year old. Nevertheless, the hierarchy of the different levels of the taxonomy remains the same.

In this way, Bloom’s taxonomy is related to Bruner’s notion of the spiral curriculum. This idea posits that students should return to key concepts and ideas at different points on their learning journey, each time meeting them at a more advanced stage of development. At whatever depth of cognition students access their lesson’s content then, Bloom’s taxonomy can help teachers to ensure that students are challenged.

Activities & Questioning

Activities and questioning are the fundamental tools all teachers use daily. Both activities and questioning require students to use different cognitive processes to interact with lesson content. The quality of activities set and questions asked has a direct impact on the progress that students make. By aligning these with Bloom’s taxonomy, cognitive demands are made on students, which can facilitate more challenge and help ensure rapid learning.

In the tables that follow, I provide exemplar question stems and sample activities for each level of Bloom’s taxonomy. Having made several minor changes, I have assembled these tables using ideas from Dalton & Smith (1986), adapting their work according to the revised taxonomy. Although these lists are not exhaustive, they do provide an excellent starting point for how to use Bloom’s taxonomy in the classroom.

| Remembering | |

| Example Questions | Sample Activities |

| What happened after…?How many…?

Who was it that…? Can you name the…? Describe what happened at…? Who spoke to…? Can you tell why…? Find the meaning of…? What is…? Which is true or false…? |

Make a list of the main events.Make a timeline of events.

Make a facts chart. Write a list of any pieces of information you can remember. List all the …. in the story/article/reading piece. Make a chart showing… |

| Understanding | |

| Example Questions | Sample Activities |

| Can you write in your own words…?Can you write a brief outline…?

What do you think could have happened next…? Who do you think…? What was the main idea…? Who was the key character…? Can you distinguish between…? What differences exist between…? Can you provide an example of what you mean…? Can you provide a definition for…? |

Illustrate what you think the main idea was.Make a cartoon strip showing the sequence of events.

Write and perform a play based on the story. Retell the story in your words. Paint a picture of some aspect you like. Write a summary report of an event. Prepare a flow chart to illustrate the sequence of events. |

| Applying | |

| Example Questions | Sample Activities |

| Do you know another instance where…?Could this have happened in…?

Can you group by characteristics such as…? What factors would you change if…? Can you apply the method used to some experience of your own…? |

Construct a model to demonstrate how it will work.Make a scrapbook about the areas of study.

Take a collection of photographs to demonstrate a particular point. Make a clay model of an item in the material. Design a market strategy for your product using a known strategy. |

| Analysing | |

| Example Questions | Sample Activities |

| Which events could have happened…?How was this similar to…?

What was the underlying theme of…? What do you see as other possible outcomes? Why did … changes occur? Can you compare your … with that presented in…? Can you explain what must have happened when…? How is … similar to …? What are some of the problems of…? Can you distinguish between…? What were some of the motives behind…? What was the problem with…? |

Design a questionnaire to gather information.Write a commercial to sell a new product.

Conduct an investigation to produce information to support a view. Make a flow chart to show the critical stages. Construct a graph to illustrate selected information. Make a family tree showing relationships. Prepare a report about the area of study. |

| Evaluating | |

| Example Questions | Sample Activities |

| Is there a better solution to…?Judge the value of…

Can you defend your position about…? Do you think … is a good or a bad thing? How would you have handled…? What changes to … would you recommend? Do you believe…? Are you a … person? How would you feel if…? How effective are…? What do you think about…? |

Conduct a debate about an issue of special interest.Make a booklet about 5 rules you see as important. Convince others.

Form a panel to discuss views, e.g. “Learning at School.”. Write a letter to … advising on changes needed at… Write a report. Prepare a case to present your view about… |

| Creating | |

| Example Questions | Sample Activities |

| Can you see a possible solution to…?If you had access to all resources how would you deal with…?

What would happen if…? Can you create new and unusual uses for…? Can you write a new recipe for a tasty dish? Can you develop a proposal which would…? |

Invent a machine to do a specific task.Design a building to house your study.

Create a new product. Give it a name and plan a marketing campaign. Write about your feelings in relation to… Write a TV show, play, puppet show, role play, song or pantomime about…? Design a record, book, or magazine cover for…? Sell an idea. Devise a way to… Compose a rhythm or put new words to a known melody. |

As a final example, let’s take a look at a stepped questioning activity, in which a series of questions are asked (written down or verbally) that gradually move up the levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. Such an activity could be carried out during one single lesson:

- What can you remember about the story? (Remembering)

- Summarise the story in your own words. (Understanding)

- Suggest how the main lessons in this story could help other young people. (Applying)

- Why did the different characters in the story behave the way that they did? (Analysing)

- Evaluate the strength of the main character’s decision to leave. (Evaluating)

- Rewrite the ending of this story, to show a different outcome. (Creating)

The framework is logical: each question becomes increasingly more challenging in terms of the cognitive demand placed on students. Stepped questions like these can be set as a single activity, with students working individually or in pairs. There is differentiation by outcome, as some students will get further than others, depending on their prior knowledge and understanding.

As all these examples highlight, Bloom’s taxonomy provides a strong basis for tailored questioning and bespoke activities, in which we adapt and modify questions and activities in order to more closely meet the needs of the students. For instance, the teacher could start with a series of ‘remembering’ (knowledge) questions or activities before moving onto a set that focus on comprehension. It may well become apparent at this stage that the students are getting stuck at this level. The point is, depending on the answers elicited, the teacher can move up the taxonomy more quickly or more slowly until the appropriate level of challenge is reached. Having arrived at the appropriate level of challenge, successful teaching would pursue question stems and relevant activities such as those listed, to help push students’ cognition, or to help them become unstuck in areas that were previously too challenging.

[1] The original Bloom’s taxonomy was revised in 2001 Lorin Anderson and David Krathwohl. Among several changes made, the revision uses verbs (Remembering, Understanding, etc.) instead of nouns, providing learners with clearer objectives for what is expected of them. ‘Synthesis’ was replaced with ‘Creating’, and the new version also swaps the final two levels, Synthesis/Evaluation, making ‘Creating’ the ultimate level achievable. Lorin Anderson and David Krathwohl were well placed to make these revisions; Lorin Anderson was Benjamin Bloom’s former student, and David Krathwohl was one of Bloom’s partners who helped to devise the classic cognitive taxonomy. I refer here only to the new version.

References

Anderson, L. W & Krathwohl, D. R., eds. 2001. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Allyn and Bacon.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., Krathwohl, D. R. 1956. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Gershon, M. 2015. How to use Bloom’s Taxonomy in the Classroom – The Complete Guide.