As part of my studies for the Certificate in School Management & Leadership with Harvard University, I share my notes here from the Leading Learning module. This particular module is about developing the school systems and culture to facilitate excellent teaching and learning.

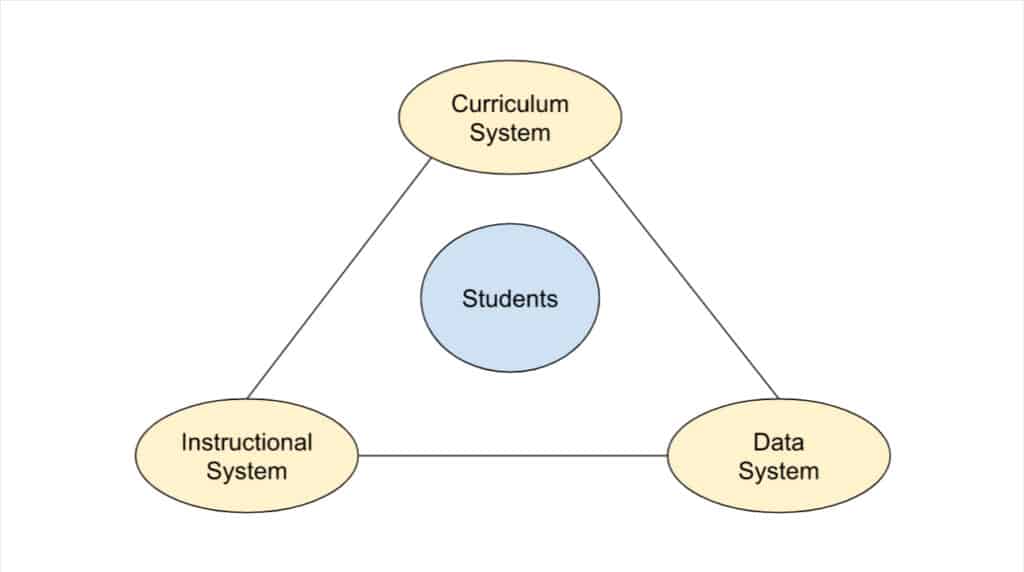

In terms of teaching and learning, there are three systems in schools: the instructional system, the curriculum system, and the data system. Each of these systems can be effective independently, but they are best when they work together and affect each other. Students are at the centre, as they are the reason why these systems exist.

Each of these systems work together to facilitate the education of students.

If any part of the system is weakened or misaligned, the educational leader must make necessary adjustments to get back on track.

For example, misalignment in the curriculum system might look like when activities in lessons do not match curriculum objectives. Curriculum alignment is well organised and designed to facilitate learning, free of academic gaps, and aligned across lessons and year groups.

Misalignment in the instructional system might look like teachers not having the skills and training to teach complex texts. Instructional alignment means engaging teachers in developing new skills.

When the data system is misaligned, it is not providing information for the educational leader to clearly diagnose gaps at the school. Data system alignment should collect data that will allow educators to understand the gaps at the school and take action on realigning all three systems.

When all systems are aligned as they should, every child in the school is surrounded by high expectations and skilled teaching.

Universal Design for Learning

It is a school leader’s responsibility to build flexible systems and structures that prioritise problem-solving and equity, using all resources available to understand the needs for all groups of students.

One way a school can become such an organisation is to implement Universal Design for Learning. Universally designed systems in schools are guiding practices that provide flexibility in ways students engage, benefitting all students.

In summary, Universal Design for Learning provides a framework for guiding educational practice that:

a) provides flexibility in the ways information is presented, in the ways students respond or demonstrate knowledge and skills, and in the ways students are engaged. For example, information may be provided in a variety of formats, such as text, audio, video, and hands-on learning.

b) reduces barriers in instruction, provides appropriate accommodations, supports, and challenges, and maintains high achievement expectations for all students, including students with disabilities and students who are English language learners. This can mean, for example, giving students more than one way to interact with material and to show what they are learning. Students might choose between taking a pencil-and-paper test, giving an oral presentation, or doing a group project.

Universal Design for Learning is underpinned by the principle of engagement. Teachers are encouraged to look for multiple ways to motivate students. Some ways are to have students make choices about assignments that feel relevant to their lives, allowing them to get up and move around the classroom, and providing options for movement like flexible seating and flexible grouping.

By effectively meeting the diverse needs of all your students, including students with disabilities, through individualised and innovative teaching practices, Universal Design Learning facilitates inclusive education.

In addition to Universal Design for Learning, teachers should be familiar with Bloom’s taxonomy, which is a practical tool to use, providing a framework in which to plan challenging lessons that help to ensure students’ progress is maximised – a fundamental tenet of successful teaching.

As I explain in my article, ‘Applying Bloom’s Taxonomy to the Classroom’, Bloom’s taxonomy provides an excellent foundation for lessons, as it can be used as a framework in which to deliver appropriate activities, assessment, questioning, objectives and outcomes.

The Importance of Writing for Students

Of all the language arts skills—listening, speaking, reading, and writing—writing is the highest, most challenging, and important skill. However, writing is often a skill that students do not get to practise frequently enough in the classroom. A recent research brief by the Learning Agency Lab found that “just a quarter of students in middle school and high school write for at least 30 minutes a day, a minimum standard set by learning experts for the development of writing skills.”

As educators, it’s imperative that we ensure students are writing enough in their day-to-day activities. Writing makes students think. It forces them to take a position and defend it. It helps them develop and demonstrate the ability to understand, weigh, decide, analyse, and synthesise. It also helps them learn to persuade, to support their ideas with evidence, and to show they know the difference between facts and opinions.

In today’s digital world, where texting and instant messaging are the norm, it’s more important than ever that students learn to write clearly and logically and for different purposes and audiences. Moreover, writing helps develop our brain’s ability to focus and promotes long-term memory.

The evidence suggests that students need three things to develop their literacy skills:

- Regular practice with nonfiction texts

- Reading, writing & speaking in evidence from the text

- Building knowledge through content rich nonfiction

One of my own initiatives in school to improve students’ writing outcomes has been to set up blogs for our students. The blogs have provided each child with an opportunity to put together a purposeful collection of their best written work as well as helping to record their learning journey. You can read more about my experience creating these blogs for students here.

The Benefits of Discourse for Students

Research has also shown that having strong discourse between students can positively impact several important academic outcomes, like increasing students’ test scores, engagement, and reading comprehension. Student discussion is also how educators can really understand and evaluate the impact of their teaching.

However, when researchers quantified how much of classroom time is actually spent on giving students the opportunity to have a discussion, the numbers were relatively low. In most classrooms, an overwhelming majority of the time is spent on what University of Melbourne professor and education researcher John Hattie refers to as “teacher talk.” Hattie found that on average, “teacher talk” accounts for “70% to 80% of the class time.” This demonstrates that despite the importance of student-level discourse, there is a gap that exists in many schools today. I have written a summary of John Hattie’s research here.

Getting students to meaningfully engage in discourse can be incredibly powerful. This is because strong discourse is built on students’ ability to connect, respect, and understand one another. However, for this type of connection to occur, and for these meaningful conversations to take place, students must be able to really listen to one another.

The skill of listening, truly listening, is quite profound. It includes several elements like eye contact, reading facial expressions, and reflecting back what one has heard in a way that conveys understanding and that checks for understanding. And when students are able to listen deeply, this not only further

develops skills in discourse and academic discussion, but it also develops students’ capacity to be empathic and caring.

The Role of School Leaders

As school leaders, the work you do is to benefit the student, but the focus of the work is on improving and supporting the practice of adults you lead. The vision and strategy is built around a simple belief: My actions as a principal can positively impact the practices of educators so that teachers can have more impact with the students they serve.

Some teachers may prioritise the act of teaching content as opposed to focusing on ensuring that students are learning the content. If teachers have this mindset, they will likely need support in changing it. That is why it is the leader’s responsibility to begin pushing the conversation about learning gaps past the level of what students are and aren’t doing to look at what teachers

are and aren’t doing.

These types of conversations can be difficult, and faculty may be resistant to owning learning gaps. Yet, these conversations must take place.

To help guide these conversations, school leaders should consider evaluation questions to gather information and reflect on what needs to improve. It also includes questions around systems and structures alignment and the work that a school leader needs to do to better support teachers to drive outcomes for students.

Examples of Evaluation & Structural Alignment Questions:

What needs to change to help all our students learn at high levels?

Do you have the data collection systems in place to get the level of information required to understand students’ needs?

What are teachers doing (or not doing) in their instruction that is helping or hindering students’ performance?

Has time been allocated for teachers and school leaders to understand and use data?

What are you doing (or not doing) as a school leader that is helping or hindering teachers’ performance?

Are instructional tools and curriculum aligned with the stated vision for the school?

There are key best practices leaders can keep in mind when facilitating data discussions:

1) Ground the conversations in data. By using student work as evidence in data conversations, as well as an exemplar to compare it against, discussions between faculty can be focused on specific gaps instead of on personally charged assumptions.

2) Encourage faculty to own the process of interpreting the data. Giving teachers the answers before they have a chance to reflect may cause them to feel disconnected from the process and may make them less likely to change their practices.

3) Support faculty by modelling data analysis if they are struggling to own the process and change their practice.

4)Hold teachers accountable to changing their teaching. Ultimately, it’s the responsibility of the leader to motivate, inspire, encourage, and support their faculty and do whatever is necessary to ensure instructional improvement through enhanced teaching.

Studies of high-performing schools show that there are several factors that must be in place to achieve school-wide system alignment to promote inclusive education:

- A strong inclusive vision

- Distributed leadership

- Structures for collaborative problem-solving

- Strong relationships with parents and the community

- Reforms situated in the instructional core

- Support for school-level universal design for learning at the school and classroom levels

Creating a Strong Instructional & Caring Culture

A culture is the integration of espoused norms and beliefs and enacted behaviours and practices, and a strong culture is one where those things are in alignment.

In a culture of caring, students are supported in caring for each other and expected to do so, including caring for those who are different from them in background and personality and other characteristics.

The way leaders can begin building a robust culture of caring is to focus on relationship development and the way that faculty and staff relate to and support students. If school staff are able to model the school’s core values and caring behaviours with students, then students themselves will be able to model it when interacting with peers and other adults.

As the school leader, oftentimes when you see a problem in the classroom, it’s really the symptom of a deeper, fundamental issue. This means you should have a defined process in place for digging deeper into the problem of practice. This process could include using tools like rubrics, conducting walkthroughs, and looking at more detailed student data.

After pinpointing the instructional gap and gaining a greater understanding of the problem, leaders can begin to engage their faculty in the process of tackling the challenge. This step is crucial, because in order for teaching and learning to improve, teachers must be engaged and held accountable for learning gaps. The conversation should shift from “what” students aren’t learning to “why” they aren’t learning. And although these conversations with faculty may be difficult, there are some key best practices to keep in mind to increase the likelihood of success: 1) Ground the conversations in the data; 2) Encourage faculty to own the process of interpreting the data themselves; and 3) Support teachers by modelling proper analysis. After going through the analysis, the key is then to move to action and actually change instruction.

When setting new goals and moving towards progress, it’s also key for leaders to be focused on how to make the work and the processes sustainable. This can be done by celebrating the small successes along the journey and letting staff and students know that their efforts and hard work are seen and appreciated.

Building a Culture of Collective Learning

School leaders have the power to create a culture of continuous improvement.

They can lead by example and role modelling, openly talking about the importance of continuous improvement, consistently asking for ideas and responding to them, and empowering faculty to make incremental improvements in their daily work.

When facing a community of teachers who have not yet bought into the goal of constantly improving student outcomes, leaders who focus on the “why” are able to build shared instructional leadership.

Involving teachers in sustained dialogue and decision-making around issues central to teaching and learning will lead to a culture of collaboration and continuous improvement.

Principals can establish school-wide mechanisms for faculty development that cut across all of the schools’ grades, such as a professional learning committee.

Seeking out champions is another effective strategy. Champions are those in your community who are enthusiastic about improvement, can provide input, and can become part of a group that tackles challenges.

Teacher Learning to Increase Student Learning

Creating a vision and communicating that vision are also important steps. Connect the vision to critical aspects of your school’s work like teacher development, collective learning, and staff empowerment, and communicate it frequently and powerfully.

Interdisciplinary teams in schools are powerful because they can attain a level of creativity and breakthrough that cannot be achieved by a single-discipline team.

When implementing a new system at your school, always start with the willing–faculty or staff who have demonstrated an interest in going through some kind of training or professional development.

There is often significant tension in schools between development and evaluation. School leaders need to be strategic, thoughtful, and transparent about when they are visiting a class for developmental purposes and when it’s a formal evaluation. To alleviate tensions, build a culture of trust and collaboration, and be approachable, respectful, and supportive.

When teachers are learning new practices and approaches, the school leader is responsible for creating the space for learning, feedback, and practice while holding them accountable for making changes in their teaching.

Leveraging Innovation and Technology for Learning

Leaders today have an especially important role to play in technology use in their schools, given its impact on nearly every aspect of our lives and our students’ education. It is important to ensure that teams integrate technologies and innovations with the goal of making teaching and learning more robust.

When integrating any innovation or new technology, evaluate its purpose and ask, “What’s the underlying theory of change for the implementation of this technology or innovation?” As you learned in Module 1, clearly aligning new initiatives to your mission and goals is critical.

To be most successful in implementing a new technology or innovation, use co-creation. Involve the people who will be implementing the change and make sure any technology initiative is practical and “people-centred.”

When implementing a new initiative in your school, remember the Cuckoo Effect. Coined by Peter Drucker, the Cuckoo Effect says that “any foreign innovation in a corporation will stimulate the corporate immune system to create antibodies that destroy it.” In other words, the dominant force of an organisation—its existing vision, systems, structures, and culture—tend to prevail over a new paradigm. To avoid this effect and give a change initiative the best chance for success, you can provide extra support and flexibility to the team implementing the change, freeing them from aspects of the organisation’s dominant systems and culture that may hinder their progress.

Leader as Learner

Great leaders focus on their own development and constantly seek out learning opportunities. Being a learner is about trying new things, welcoming feedback, and seeking out other points of view, even when it’s difficult. An avenue for principals to learn is exploring resources outside of school, such as a forum connecting principals in your district, or a national association for principals who are committed to the

ongoing development of school leaders.

To Model Learning at Your School:

– Spend more time in learning activities.

– Ask more questions.

– Don’t assume you know everything, and don’t be afraid to make mistakes.

– Ask for feedback.

– Encourage others to experiment, take risks, and accept failure.

Family-School Partnerships to Support Student Learning

Families play a crucial role in student learning. When families and school teams work together, they can jointly support students’ education, health, and development.

Research shows that the level of family engagement within a school can have a significant impact on student outcomes. It’s linked to higher academic achievement, better student behaviour, and enhanced social skills. It can increase graduation rates, test scores, and attendance.

When it comes to engagement in your community, what matters most is that you adopt a partnership mindset—recognising that families are key contributors to the success of your students and school—and that you regularly seek out opportunities for strategic family-school partnerships that will support your students and school in achieving their goals.

Concluding thoughts…

It is the role of the school leader to ensure that all teachers have high expectations and the skills to implement those high expectations. This requires the systems to develop, support and monitor teaching and learning in the school. Systems and structures, in fact, are the key ingredients in making any organisation function at a high level, and strategic alignment — as well as continuous realignment of capabilities, resources, and management systems — needs to happen to maintain that level of achievement. When designing whole-school systems and structures, it is important to be flexible and keep standards high by using principles of universal design to support and serve all students.

The term “culture” can be used to describe both the instructional practices in a school, as well as the relationships between adults and students and the level of caring within a school. It is the role of the school leader to help establish and maintain a school-wide culture that supports continuous improvement. After all, building a culture of positive continuous improvement and learning

is at the heart of every successful school.

Learning never ends, and school leaders have the power to be role models by embracing the practice of

the leader as learner.

Technology, when used purposefully and in alignment with your school’s goals, has the potential to improve teaching and learning at your school and broaden experiences and opportunities for your students.

Finally, students’ families are critical partners in achieving success for your students and school, and that engaging families strategically and respectfully can positively affect academic outcomes.