Last month I completed the Harvard Business School Course, Leading Change. I share here my key notes and takeaways from this course:

1. Identify Adaptive Challenges & Apply Adaptive Solutions

One of the core ideas underpinning this course, Leading Change, is that complex projects are what can be referred to as “adaptive challenges” which require an adaptive leadership approach.

So, what is an adaptive challenge? An adaptive challenge is a non-routine challenge that requires development of new capacity. Adaptive challenges are not clearly defined and cannot be clearly solved with existing know-how alone.

For adaptive challenges there is often not one right answer and no expert has the answer by themselves. The people with the problem must solve the problem, sometimes reaching beyond what they already know how to do. This means that new learning must take place on the part of those looking to solve the adaptive problem. It also means providing specific ways to allow for distributed leadership, to include others in the school as leaders.

By contrast, a simpler (non-complex) challenge can be defined as a technical problem. Technical problems are those that can be diagnosed and solved, generally within a short time, by applying established know-how and procedures.

Being able to distinguish between technical and adaptive challenges helps you to know which approach to use when solving them.

The question then becomes this: how can you tell if a challenge is primarily adaptive or primarily technical?

|

Kind of Challenge |

Problem Definition |

Solution |

|

Technical |

Clear/Known |

Clear/Known |

|

Adaptive |

Unclear |

Requires learning |

In schools, we know that family engagement is important for student advancement. Finding ways to effectively engage parents in students’ academic work often proves more challenging.

The two most crucial characteristics of an adaptive challenge are that the problem definition is unclear and the solution requires learning. But there are additional characteristics that can help you identify adaptive challenges.

Adaptive challenges typically display one or more of the following characteristics:

|

The language of complaint is used increasingly to describe the current situation. |

|

Previously successful outside experts and internal authorities are unable to solve the problem. |

|

Frustration and stress manifest and failures are more frequent than usual. Traditional problem-solving methods are tried without success. |

|

Rounding up the usual suspects to address the issue has not produced progress. |

|

The problem festers or reappears after a short-term fix is applied. |

|

Increasing conflict and frustration generate tension. A willingness to try something new builds as urgency becomes more widespread. |

|

A sense of crisis is often symptomatic of an unresolved adaptive challenge. |

Critically, an adaptive challenge means that the people with the problem have often become part of the problem. Their ways of thinking, their habits and their relationships established in response to their environment all begin to contribute to the current equilibrium. Yet – while the people are part of the problem – they are also essential to the solution.

Working through this adaptive set of challenges is not easy because, in most settings, it is hard to ask people to own a challenge they think others should solve or to push the frontier of their current competence.

A common mistake is that when the problem and solution are within your expertise as a leader, that you end up micromanaging.

Exerting expertise, taking the problem onto your own shoulders, and applying a technical fix, can be really tempting.

It is the most common source of failure in leadership – treating adaptive challenges as though they were technical problems.

It often stems from the leader not recognising the issue at hand is an adaptive challenge, which cannot be solved with existing methods or knowledge. Learning to identify adaptive challenges and applying adaptive solutions is a key component of successfully leading change.

When I reflect on my own experiences as a school leader, one of the biggest challenges that I have faced has been dealing with people who have negative attitudes and ways of thinking. This, at times, has made it difficult to implement the key changes necessary to positively impact student learning.

On the subject of dealing with “difficult people”, this quote from the ancient Roman emperor, Marcus Aurelius resonates with me:

When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous and surly.

Marcus Aurelius, who recorded this passage in his personal diary, certainly had his fair share of difficult people – but he goes on to explain that, however bad other peoples’ behaviour, the important thing is not to take anything personally.

Remember, when you lead, people don’t love you or hate you. Mostly they don’t even know you. They love or hate the positions you represent” (Heifetz 2017, 198).

Therefore, “when you take ‘personal’ attacks personally,” or when you give in to flattery, “you unwittingly conspire in one of the most common ways you can be taken out of action—you make yourself the issue” (Heifetz 2017, 191). The key to handling this potential setback is to place the focus back where it should be: on the message and the issues.

As a leader, among the adaptive ways of thinking and behaving that I have adopted for myself – when faced with these particular challenges – are summarised in these three key suggestions from the course:

- Lead with questions rather than answers

- Frame the right questions, e.g. Ask teachers: what do I need to do make this work your own?

- Generate capacity on the part of staff rather dependency.

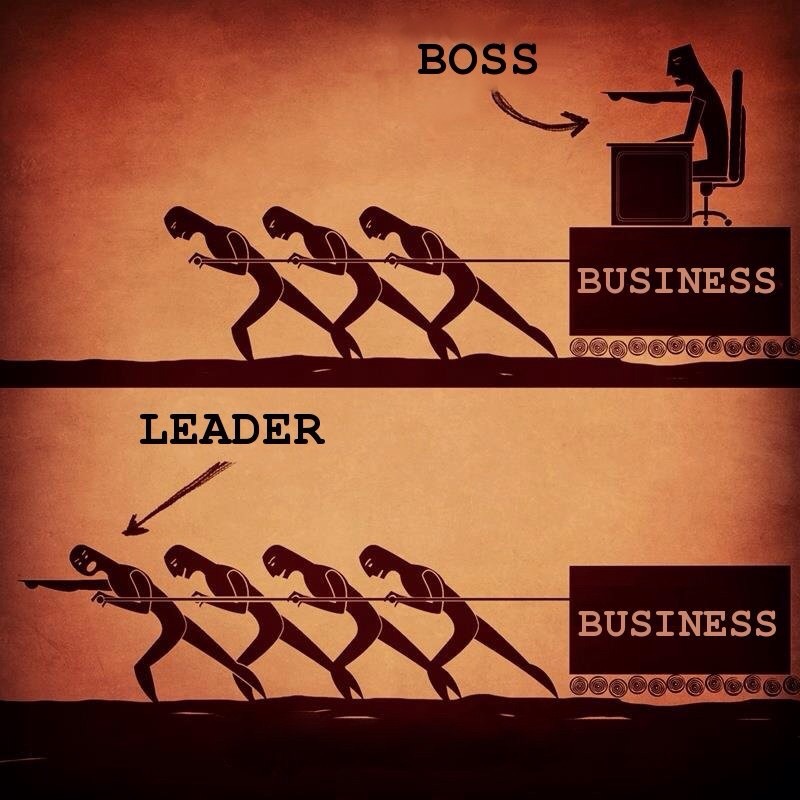

2. Recognise that “Authority” and “Leadership” are distinct

Authority is when a person is entrusted with a position of power in order to provide a service – usually some level of direction, protection and order. Leadership, on the other hand, is more than a position of authority – it is your ability to influence others to solve adaptive challenges.

Qualities traditionally associated with leadership such as charisma, confidence and determination are powerful strengths and can be considered key sources of your authority in people’s eyes – but they only serve you as a leader if you draw on those strengths and authority to tackle adaptive problems.

The idea that leaders are born and not made, is quite dangerous. Those who consider themselves born leaders, free of any strategy of leadership, are set up for a tough awakening and have the potential to do great damage. Conversely, those who don’t consider themselves leaders escape responsibility for taking action or for learning how to take action when they see the need.

This quote about leadership from the Harvard course really resonated with me:

‘Leadership is the practice of mobilising people to tackle tough challenges, framing the key questions and creating the conditions to enable them to make progress.’

In other words, leadership mobilises people for adaptive work.

Leadership is necessary when we face adaptive challenges that cannot be solved with technical solutions alone. If we lived in a world with only technical challenges, we would only need authoritative expertise.

‘In this framework, leadership is a practice, an activity – and not by itself a set of strengths, position or toolkit… Sometimes people in authority lead but sometimes they do not. Likewise, sometimes people with no authority provide extraordinary leadership by moving the ball down the field.’

3. Lead Adaptive Work

-

Use the tools of your authority

Practically speaking, recognising the distinction between authority and leadership means that you can be more strategic in using the tools of your authority in your practice of leadership. Moreover, the fact that leadership is a practice and not an authority position means that many can participate by working together, drawing on one another’s strengths to tackle adaptive challenges.

As leaders with recognised authority positions, we must encourage teachers to lead each other to improve teaching.

Some people in authority though, choose not to address adaptive challenges (for fear of failing) and therefore choose not to lead.

To make this distinction between adaptive problems and technical problems, we must ask ourselves, “Does making progress on this problem require changes in people’s minds, hearts and behaviours?”

(What I realise now is that much of the work of a leader is to “Change minds, hearts and behaviours”!)

If the answer is no, then it is simply a case of using our authority alone to apply an expert solution, or delegate that responsibility to someone else with the appropriate expertise. However, if the answer is yes, we have to engage in leading an adaptive process.

Ultimately, everyone will trust you more for creating a more hospitable environment for addressing adaptive challenges. This means using your authority to provide presence, structure, and hope while maintaining your own personal confidence and poise. In addition, you should keep an eye out for ways to frame the key issues for the upcoming adaptive phase.

Above all, hold steady and keep your spirit in the game. Throughout a crisis, the prospect of addressing the adaptive challenges represented by the crisis may be daunting, but with persistent effort and time you can transition into the adaptive phase.

-

Identify challenges that are ripe for change

Identifying which issues are ripe to be tackled is very important. With ripe issues, there is a shared sense of urgency and a large proportion of people in an organisation will be more easily galvanised into action. Although people may disagree about how to move forward, they will agree that something needs to be done. With unripe issues, a single group of people will feel passionately that something needs to be done, but other groups will disagree. In the most extreme cases, no one will have noticed the challenge or attempted to resolve it. Addressing an unripe challenge wastes time.

-

Ripen challenges that are unripe but important

Sometimes it is necessary to help urgent challenges ripen. Urgency, when it is well framed, promotes adaptive work ripen challenges more quickly. You can help ripen a challenge by drawing attention to it and using data to illuminate its various facets.

Be careful not to try to solve adaptive challenges alone, even in a time of crisis. While you can and should use your authority to restore order or safety if necessary, once order is restored, it’s imperative to involve other members of your community as leaders. Remember that a crisis can serve to galvanise support and create a sense of urgency that can be used to get others to join you in adaptive problem solving.

When you bring together people who are passionately committed to a particular issue but have different perspectives, you have conflict. You want to harness these natural conflicts to produce new ideas and bring about collaborative learning.

-

Create a ‘holding environment’

To help people in the challenging process of adaptive work you need a ‘holding environment’. The holding environment is a network of relationships that holds people in the hard sometimes divisive work of problem solving.

A good analogy is that of a pressure cooker to describe the holding environment to accelerate the mixing of people and ideas which is facilitated by a leader.

The very first holding environment we encounter in life is between a parent or guardian and a child. Anyone who has been a parent or caregiver can appreciate the work that is involved and the strength of the bond needed to nurture a person you care about until they make their way out into the world to support themselves. This bond is formed not only out of love and devotion, but out of a desire to build that person’s capacity to thrive in the world. For adaptive work in a school, which can generate similar growing pains, the holding environment will keep stakeholders engaged in difficult conversations until solutions are implemented.

For schools, a shared desire to help children achieve their potential helps create and reinforce the ability to tolerate the heat of adaptive change. A shared commitment to excellence, a common professional vocabulary, a shared history at a school, and even a comfortable room to meet in can help strengthen the holding environment. An additional element—trust—is essential for strong holding environments.

A holding environment consists of vertical and horizontal bonds of trust.

To lead you must continually strengthen your holding environment by strengthening your bonds of trust.

Vertical and horizontal bonds are not static—they can be built or dismantled over time. As the school leader, you can contribute to building strong horizontal bonds of trust among your teachers and staff. Intentional practices, such as professional development days and community building activities, are effective. Even less formal approaches, such as providing a welcoming and comfortable atmosphere and work spaces, can be conducive to strengthening horizontal bonds among coworkers.

By assessing the adaptive capacity of your school, selecting ripe challenges, finding your school’s assets and seeds of innovation, and strengthening the holding environment, you are creating conditions that will support the school’s adaptive work.

Before you go public with your initiative, you need to line up enough support to keep your intervention alive once the action starts.

-

Find allies and distribute leadership

Adaptive problems cannot be solved primarily using authority and expertise, and you cannot take the burden entirely upon your own shoulders. As a leader with authority in your school, you must seek out and encourage leaders from all levels of the organisation as you address your school’s adaptive challenges.

In addition to identifying like-minded persons as allies, seek out less likely potential strategic allies—those who, if persuaded to join you, could substantially impact your ability to accomplish your goals.

For adaptive challenges you undertake in your school, finding allies eager to innovate will be easier when issues are ripe and ready to be addressed. Through a process of observation, you may have already identified parents, students, teachers, or staff eager to address a challenge that would advance progress toward a shared goal.

But keep in mind that an alliance does not necessarily translate into loyalty. Allies may be aligned with you for a variety of reasons, but they could also have other potentially competing alliances, constituents, or conditions. Therefore, your allies need to be nurtured and not taken for granted. Seek to understand and honour these other loyalties.

It may be difficult and take time, but doing so is critical to sustainable change. Without these alliances, the risk is greater that your changes will be reversed once you leave the building.

-

Celebrate small wins

Publicising and celebrating small wins in your school will help build momentum for the long and sometimes difficult road of change. Planning for and executing early quick wins can also help build the community’s trust in your leadership abilities.

You may even build wins into the change process by designing achievable early milestones. It is important to share early wins, even small ones, strategically. At times you might choose to communicate less publicly through formal or informal conversations with individuals or groups. I have done this, for example, by publicly praising colleagues in meetings, by email and using a school blogging platform.

While your allies will appreciate the recognition they receive, keep in mind that they are not your only audience. Sharing wins should also be done as a means to encourage others to engage in the work.

-

Listen to the ‘Song Beneath the Words’

The Song Beneath the Words expression refers to the underlying meaning or unspoken subtext in someone’s comment, often identified by body language, tone, intensity of voice, and the choice of language.

As you observe in your daily practice, pay attention to cues, body language, and the facial expressions of those around you. You probably already do this on a daily basis. If you ask someone how their day has been and they say, “Okay,” you can search for clues to sense how they are really doing through their tone and facial expressions. As a school leader, you should be especially sensitive to this subtle language. Teachers may feel obligated or have professional aspirations that compel them to say certain things or agree with you in meetings. However, their true opinions and beliefs will become apparent in their actions and through careful observation of unspoken cues.

-

Take a step back

Every so often, remove yourself from a situation in order to gain perspective on the work dynamics at play. Try to make your observations as objective as possible, e.g., what are people reacting to from their vantage point that shapes their perspective? Practice carefully observing before you interpret what you see. Consider multiple possible interpretations by asking others what they see and how they interpret the situation, particularly if the issue is important. This will help you and others develop a more complete picture and objective understanding of the issues as you and they integrate multiple perspectives into the work.

When change is clearly positive people embrace it. What people resist is not change per se, it’s loss – or the risk of loss.

You can help others endure their losses by recognising them and honouring them. Reminding them of the bigger values at stake will help them through the transition.

-

Acknowledge Losses

As a leader, you should not pretend that losses do not exist. Instead, acknowledge the losses of your staff and community during the process of change by validating their feelings. This is one way to court the uncommitted. Recognising losses shows that you understand and appreciate the real sacrifices some are making, and that you appreciate their willingness to move forward anyway. Related to this strategy, you can generate further trust by taking losses yourself. For example, if teachers give up their time in the afternoons, evenings, or during vacations to participate in professional development meetings, you could attend all or part of the sessions to show your support and solidarity.

-

Accept Responsibility

In addition to honouring loss, uncommitted parties will also want you, as the leader, to acknowledge your responsibility in contributing to the problem. Accepting responsibility for some part of the problem will show those you lead that adaptive change is a collective and collaborative effort. It will also show them that it is okay to be vulnerable with colleagues and own up to mistakes. As you accept responsibility, you will be perceived as a more trustworthy leader. Modelling the behaviours you are seeking in others will encourage them to emulate you, and it will make you more authentic in their eyes. This also helps engender trust as you engage in the difficult work of learning together.

-

Orchestrate Conflict

Working through conflicts allows different viewpoints to be synthesised and new learning to take place. Establish ground rules for discussions; get each view on the table; manage tensions and keep people engaged; encourage people to accept necessary losses; generate and commit to experiments; and institute peer leadership consulting. Your job is to manage the conflict so that the underlying issues become addressed without generating so much heat that the interactions become unproductive.

If you are strengthening the holding environment, the bonds of trust will contain the heat generated by the conflict and enable you to hold and maintain the constructive engagement of people and ideas.

“Music teaches that dissonance is an integral part of harmony. Without conflict and tension, music lacks dynamism and movement.”

In some schools, people may be used to avoiding conflicts at all costs, or they may not have the processes and skills in place to work through differences to a place of synthesis. Your role in managing conflicts will be critical. Think of yourself as the composer: you must keep the music in dissonance and hold the audience’s attention until a resolution is found.

-

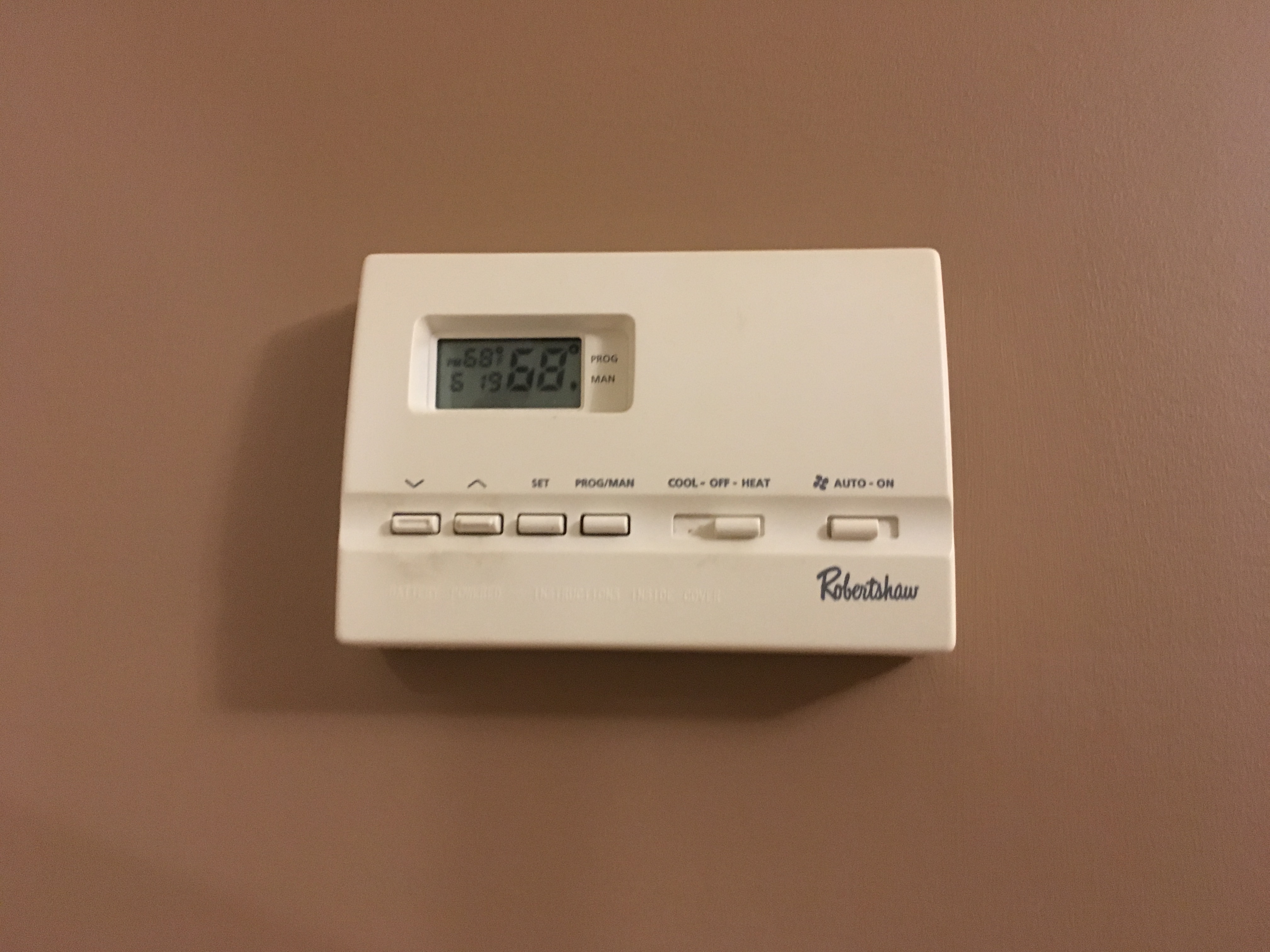

Manage the thermostat

The productive zone of disequilibrium (PZD) is the state where there is just enough stress to cause people to seek change and engage in adaptive work, but not so much as to cause them to shut down or disengage. To stay in the PZD, you will have to keep your hand on the thermostat, carefully raising or lowering the temperature as needed.

Tactics for Raising the Temperature:

- Draw attention to the tough questions.

- Give people more responsibility than they are comfortable with.

- Bring conflicts to the surface.

- Protect those with unusual ideas and divergent viewpoints.

Tactics for Lowering the Temperature:

- Speak to people’s anger, fear, and disorientation.

- Establish a structure for the problem-solving process by breaking the problem into parts and creating time frames, decision rules, and clear role assignments.

- Slow down the process. Pace and sequence the issues and who you bring to the table.

- Be visible and present – shoulder responsibility and provide confidence.

- Orient people – reconnect people to their shared values, and locate them in an arc of change over time.

- Make short-term gains by prioritising the technical aspects of the problem situation.

Letting the voices of people who disagree with you be heard and paying respectful attention to their arguments, without derailing the adaptive work, sends a powerful message to others in the organisation. Additionally, embracing aspects of their argument may actually help improve the work. This lets the community know that it is okay to respectfully speak up and voice contrary opinions that go against the person in authority. For a school to be truly adaptive, these types of exchanges must become a fabric of the culture.

-

Be intentional about taking care of yourself

You have to plan for the stresses of leadership and this means that you must, as a matter of priority, take care of yourself. There are several ways to do this:

- Find confidants – to air your frustrations. Remember though, it is often a mistake to confuse an ally with a confidant. Make sure these are separate and distinct from one another.

- Find sanctuaries.

- Do things that you enjoy – reliable activities that lift you from the workplace.

Confidants, sanctuaries and practices help us reconnect with ourselves and regain our perspective and purpose. When the going gets tough in leadership, they are essential

-

Operate at the frontier of your competence

Finally, just as you give others permission to experiment with and operate at the frontiers of their competence, you will need to do the same yourself. This will involve relying less on your authority and any initial temptations to provide all the answers. It may also involve, when appropriate, being honest with others about operating at the limits of your current capacity. This will not only allow you to develop new capacity, but will also build trust and strengthen your credibility with others.

4. Leading Cultural Change

-

Enabling Cultures

Culture can either be an enabler or an impediment to a leader’s work. Leaders can actively shape their school leadership.

Shaping school culture is a very doable and powerful leadership practice. An enabling culture is necessary for leading a successful school. When teachers’ and students’ beliefs and behaviours are in harmony with the school’s core mission, the school will be more effective in achieving its critical mission of educating all students. When these beliefs and behaviours are at odds with the school’s mission, the opposite is true.

Culture is the integration of the three dimensions—shared beliefs and assumptions as well as norms and behaviours, and artifacts (the way classrooms are arranged, how data are displayed, and what student work is on the walls)—which reinforce each other to create an overall culture.

What an enabling culture looks like may vary from school to school, but there are two essential elements that all enabling school cultures must have: (1) effective teaching and learning, and (2) equity.

For school cultures to have these two essential elements, they must be supported by all three dimensions of a school’s culture – shared beliefs and assumptions, norms and behaviours, and artifacts.

-

Enact Espousals

The leader’s job is to minimise the differences between enacted norms and espoused norms. What is left unsaid contributes to a hidden culture. People generally don’t expend much energy on things that they do not perceive the leader cares about.

Some variation within and among subcultures is to be expected, but when there is a lot of variation within and across subcultures, the sense of “how things are done here” becomes less clear. The overall culture can be confusing, unclear, and incoherent.

-

Distribute Leadership

A strong culture can also help school staff feel empowered to actively shape culture on their own. This is an effective way of distributing leadership to your staff members.

A strong culture acts like the person’s conscience; it is the sense of how we get things done. In a school with a strong culture, which reflects the desired norms and behaviours, the choice to make (e.g. about a student’s misbehaviour) will be obvious.

Changing culture, like any adaptive challenge, involves changing the hearts, minds, and behaviours of the school community. This kind of change involves difficult work and individuals will experience a sense of loss as you as your school community begin to make changes.

-

Establish a sense if urgency

Since leaders often overestimate the amount of urgency members of their community feel for need for change, it is up to the leader to establish and convey a sense of urgency in an emotional, tangible, and credible way. Use bad news as a call to action which prompts a sense of shared urgency – and never waste a good crisis. This engages people emotionally to help solve the problem.

-

Communicate a vision

One way a leader can and should make progress toward realising a vision is to make sure that everyone is aware of it. A good vision should be easy to communicate and flexible enough to allow for experimentation. In addition to the vision statement itself, the leader should also develop a short-hand articulation of the vision and communicate it at every opportunity. A simple, clear message will be powerful.

This short version of the vision is often called an “elevator pitch” because it should be brief enough to give during an elevator ride. Elevator pitches should explain “what” and “why” and they should generally have no more than three to five main points. Leaders should take every opportunity—staff meetings, parent meetings, assemblies, newsletters, etc.—to remind the community of the vision. It is also important to communicate frequently and consistently about how the school intends to make progress toward that vision, and about how it is acting upon its values. Under-communicating your vision is a common leadership mistake. Communication takes time and continuous effort, but it is an invaluable investment. Repeat your vision so many times you can recite it in your sleep!

-

Change inhibiting beliefs

When members of your school community hold beliefs that are inconsistent with the school’s desired culture, you should primarily focus on changing their behaviour so it is aligned with the culture. Beliefs themselves are difficult to change, and observable behaviours are what impact students and peers most.

The most effective approach to changing beliefs is to get people to change their behaviour regardless of their current beliefs. Remember, as a school leader, you have the right to ask teachers to try out new approaches.

Changing beliefs in your school:

- Be prepared to have honest conversations about your expectations and needs.

- Make policies and procedures compatible with desired behaviours.

- Model behaviours, attitudes, and perspectives early and often.

- Align feedback, incentives, and rewards with desired behaviours.

- Celebrate individuals whose behaviours have the widest impact.

Success is more often a wavy line than a straight one. As long as you are moving roughly northeast, you are making progress. Don’t be discouraged if changing your school’s culture doesn’t translate right away into academic change. Expect this to happen over time. This is when it’s hardest to be a leader, knowing that the changes you’ve made are going to have an impact but not necessarily throughout the school at the same time.

Shaping culture and transforming a school’s culture is a never ending process. It can take months or years to see significant, lasting effect of cultural change but it is worth the effort.

5. Building a Culture of Equity

All students can flourish and achieve at high levels if adequately supported by their classroom and school environment, regardless of their background and identity.

Equality is giving every child the same thing. Equity is giving every child what he or she needs according to the agreed standard. Equity holds that different students will have different requirements; equity means creating the conditions such that all students can thrive.

Every child is different and will have different needs. It is not enough for schools to provide the same structures and supports to students – that is, treating students equally – because this ignores their differences. Equity means creating the conditions that enable every student to succeed. Equity holds that different students will have different requirements; equity means creating the conditions such that all students can thrive.

Examples of Equity Challenges:

- Male students are not achieving the same academic standards as females.

- Students of colour are underrepresented in leadership positions and extracurricular activities

- Students with special needs are not receiving appropriate accommodations to access all subject areas or parts of the curriculum.

The work of an educator is very personal – you are helping the next generation succeed.

-

Use Data

Data is the most powerful tool we can use. A first step to addressing equity challenges therefore, is to explore and examine the data available at your school. Make a point to collect and analyse data as a collaborative process while sticking to your core belief system.

Consider diverse sources of data, including proficiency and achievement data, classroom observations, data from engagement and climate surveys, and observations from people in your community.

After identifying the equity challenge(s) that you are facing, you must:

• Define goals that incorporate high standards for all, and

• Identify a strategy to achieve the goals, reach the standards, and hold you and your community accountable.

• Addressing equity challenges requires an iterative approach based on data to assess and evaluate progress.

Creating effective systems for data collection is critical.

-

Focusing on inclusion and belonging

- As a school leader you’ll need to make sure that you build a culture that supports the success of all students. One of the biggest obstructions to achieving equity in schools is low expectations of students. There can be a culture of love – but when that love comes from a place of wishing only happiness for students rather than pushing them to achieve their best, it is impossible to achieve equity or excellence.

-

The degree to which students and faculty feel like they are welcome, included and belong deeply influences if they can perform at their highest level. Inclusion and belonging represent safety and are a human yearning.

-

Consider the background and demographics of your students, staff and community, and then identify ways in which your school can better communicate that it recognises, welcomes, values and appreciates this diversity.

-

As a school leader, you’ll need to examine how school-level and classroom-level elements communicate to your students that you and your staff believe they can succeed at high levels.

-

Many teachers do not believe that certain individuals or groups of students can perform at high levels. In some instances of low expectations, the teacher or staff member may believe that they are providing supports to meet high standards by making the work easier, but in fact what they are doing is lowering standards. When you observe either of these situations, you must intervene immediately to correct these practices.

- In lesson observations, you should be on the look out for differentiation of instruction rather than differentiation of standard. The equitable approach is differentiating by instruction which shows that we hold high expectations for our students. The alternative – to differentiate by standard – leads to a lack of rigour which communicates a lack of confidence in students’ ability to perform and thus goes against equity.

-

Foster a growth mindset

- Instilling a growth mindset in students is important to advancing equity because students who believe that their capabilities can be developed and that their intelligence is malleable are more receptive to feedback, work harder, and are better equipped to deal with setbacks.

- As a school leader, you must guide your teachers in designing activities and learning experiences that show students what growth mindset is and why it is important, and you can help them see that their own behaviour and attitude in the classroom can model for students what it means to have a growth mindset.

-

Counter unconscious bias

-

We all have some degree of unconscious bias, and without us even realising it, it affects how we interact with others. Nevertheless, we need to ensure that our unconscious biases do not limit the opportunities for our students and staff.

-

Unconscious bias can show up in different ways in schools or classrooms: the students or teachers we call on or spend time with, the feedback we give to them, the extra supports that we provide, the way we react to their successes or failures, and the special opportunities that we do or don’t make available to them.

-

As a leader, you must work with your staff and community to address the effects of unconscious bias by discussing it as a group, and also implementing specific practices to mitigate its effects.

-

In the long run, the accumulated effect of these actions is diminished opportunities and exclusion of some members of our school communities. It is fundamental that you and your team work to recognise, address, and mitigate the harmful behaviours stemming from unconscious/implicit bias.

-

Some exceptional challenges may require you to use your authority first to correct behaviours that threaten safety and equity in your school before you and your team can turn to address the adaptive elements that also require change.

Here are some suggested norms to guide a discussion on bias:

- Be willing to surface and explore unconscious beliefs and values.

- Listen to understand, not to respond.

- Be mindful that your truth can be different from that of others.

- Honour confidentiality.

- Take responsibility for your own learning.

- Be willing to think about situations and issues with a new or expanded perspective.

-

Build rapport

The importance of diversity and inclusion can be demonstrated for through small acts that can make a big difference. You can:

- Help a colleague perform their work tasks by providing information, making introductions to contacts, giving endorsements in meetings, or offering advice or guidance.

- Show an interest in a colleague’s life, hobbies, or experiences, or providing space to debrief meetings.

- Create and communicate a closer connection through body language and space-sharing such as walking to a meeting together or choosing to sit next to them at a gathering.

- Make sure your team members understand the harm of micro-aggressions and are equipped with the techniques for not using them.

- Establish a sense of psychological safety where everyone feels confident and comfortable to take risks, make mistakes, contribute opinions, and be candid about what they are up against.