In his book, The Filter Bubble, Pariser (2011) describes a digital situation we all now face in which website algorithms selectively present information to users based on location, click behaviour, search history, etc., and, as a result, distance users from information that disagrees with their viewpoints, effectively isolating them in their own cultural or ideological bubbles. In December 2009, for example, Google began using 57 different signals – everything from a user login location to their browser to their search history – to make guesses about who the user is and what kinds of sites the user would like to see. Likewise, social networking sites such a Facebook and Twitter are built on the premise that users interact with other users that they have chosen to interact with, which limits the coverage of news they receive. Although filter bubbles almost certainly provide users with information of subjective value, based on their needs, desires and preferences, they also lead users to a state of cognitive bias. This means users may dismiss otherwise potentially useful information, because it does not conform to their cognitive schema. As more users discover news through algorithm-determined feeds, important news content relevant to the public sphere falls out of view.

According Pariser (2011, pp. 4): ‘Democracy requires citizens to see things from one another’s point of view, but instead we’re more and more enclosed in our own bubbles’.

In order to be news literate on a global scale, it is surely necessary to break out of these filter bubbles by reading from a wider variety of sources from around the world.

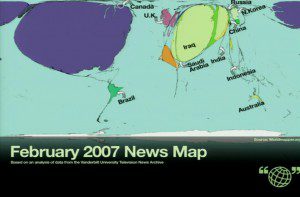

Another type of filter bubble can be seen in terms of the coverage of global news itself. Reese (2011, pp. 5) states that against the expectation that media report and reach the entire globe, the global media system, particularly international broadcasting, does not live up to that hope. For example, Alisa Miller, head of Public Radio International, presented a cartogram during a TED Conference to show how the US media covers international news.

Fig. 1

This map shown in Figure 1 represents the number of seconds US network and cable news organisations dedicated to news stories by country in February 2007. This was a month when there had been very significant international events: North Korea agreed to dismantle its nuclear facilities, there was massive flooding in Indonesia, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a study confirming man’s impact on global warming. During this month though, Miller (2007) observes the US accounted for 79% of the total news coverage; the combined coverage of China, India, and Russia represented just 1% of the news. Similar distortions in the way news is covered can be seen in elite online newspapers such as the New York Times and Guardian.

What the cartogram serves to illustrate is that, contrary to what people might think, news media does not deliver an equitable distribution of global news coverage. According to Adams and Ovide (2009), the online availability of news and the demand for larger corporate profits has driven both audiences and advertisers to cyberspace, triggering a crisis in the news industry, which is increasingly turning to local coverage. Consequently, foreign news bureaus have been disappearing, as foreign correspondents are seen at best as unnecessary “middle men”, at worst as “endangered species”. (Hamilton, 2009, pp. 463).

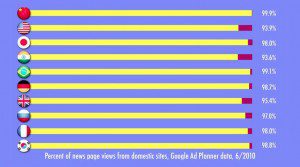

Fig. 2

As Figure 2 illustrates, the same problem can be seen on the demand side for news. On average, more than 95% of national news readership is on domestic sites. Citizens in the UK, for example, are unlikely to read about news happening in Australia on an Australian website. Instead, they are far more likely to read about events in Australia, filtered through a UK news outlet, such as the Guardian. Language can be an obvious barrier here, preventing readers from visiting foreign news sites. With relatively high numbers of immigrants, this may explain why the US and UK have comparatively more of their citizens viewing foreign web pages than China, for instance, which has proportionally fewer immigrants.

Nonetheless, the fact that the vast majority of page views are on domestic news sites for all countries is considered by Zuckerman (2010) to be a serious problem:

‘The real problems in the world are global in scale and scope; they require conversations to get to global solutions. This is a problem we have to solve’.

Moreover, when foreign news is reported by a domestic outlet, true comparative analysis is rare. News, according to Reese (2012, pp. 2), is ‘still domesticated through national frames of references, often taken for granted, and media globalisation skeptics have argued that no truly transnational news platforms have emerged, permitting the kind of cross-boundary dialogs associate with a public sphere’. Media sceptics such as Hafez (2007) point to the continued weaknesses of international reporting: ‘elite-focused, conflict-based, and driven by scandal and the sensational, leading them to conclude that the “global village” has been blocked by domestication’.

As so much of our news now comes from online sources, we need to ensure that our students have the digital literacy skills needed in order to become well-informed global citizens. If they lack these skills, then we cannot truly claim to be providing an education that facilitates the often touted ideal of “international mindedness”.

References:

Adams and Ovide. 2009. Newspapers Move to Outsource Foreign Coverage. The Wall Street Journal, 15 January.

Hafez, K. 2007. The myth of media globalization. Malden, MA: Polity.

Hamilton, J. 2009. Journalism’s Roving Eye: a history of American foreign reporting, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press

Pariser, E. 2011. The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think. Penguin Press.

Miller, A. 2007. Ted Talk: The News about the News. http://www.ted.com/talks/alisa_miller_shares_the_news_about_the_news.

Reese, S. 2012. Global News literacy: The Educator. Global News literacy: The Educator (Chapter prepared for News literacy: Global perspectives for the newsroom and the classroom). University of Texas at Austin.

Zuckerman, E. 2010. Ted Talk: Listening to Global Voices. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vXPJVwwEmiM