My vision for News on Atlas is and has always been to provide a tool to improve the news literacy and international-mindedness of users. I think it’s worth exploring other initiatives that have had similiar aims in order to highlight the potential usefulness of News on Atlas. Having researched this area a lot, I have found two prominent examples in recent years of efforts to integrate such lessons into the classroom, The Powerful Voices for Kids Program and the News Literacy Program at Stony Brook University. I discuss these examples here:

1. The Powerful Voices for Kids Program – Hobbs (2010)

Powerful Voices for Kids participated in a university-school partnership involving Temple University students working with small groups of children (ages 9 to 11) to develop their news literacy skills during July 2010. The young age of the participants made this program particularly unique. According to Powers (2010, pp. 2) targeting students still in compulsory education is wise, because these are the years when many people begin developing reading and viewing routines. The younger news literacy can be taught the better. Hobbs (2010) observed this program closely, reporting it to be a perfect example of “what works” in news literacy education, and she uses this to draw fundamental learning principles that should guide the pedagogy of news literacy.

Hobbs focuses specifically on one group of children who were involved in a project where they explored just one news story in depth: the violence associated with flash mobs in Philadelphia. Using the simple programming tool, Scratch, the children made interactive media about the news event, which stimulated conversation about how the news is constructed and why news is important in society. Hobbs (2010) reveals key learning outcomes of this project for the children, which made them more aware of the role of news in society, how to assess its reliability and the impact news can have on others.

Commenting on the outcomes of the program, McManus (2009) states that:

‘In my view, these are the kinds of insights that are now essential for people to be full participants in contemporary society. These are habits of mind that will enable young people to flourish in the tsunami of information that surrounds them, where news pretenders offer “fake news” and where cheapening and corner-cutting interfere in cash-strapped news organisations leads to a diminution of quality news and information’.

According to Hobbs (pp. 4), the success of the program was achieved by building critical thinking and communication skills. In contrast to the transmission model of education, the program begins from the learner’s interests: ‘Learners, not teachers select the topic to examine, and they select news that’s personally meaningful to them’. In the teaching process, students are also encouraged to ask critical questions, using reasoning and evidence to support their ideas. This method is particularly appropriate for the area that Hobbs refers to as ‘constructedness’, in which careful attention is paid to how news stories are constructed.

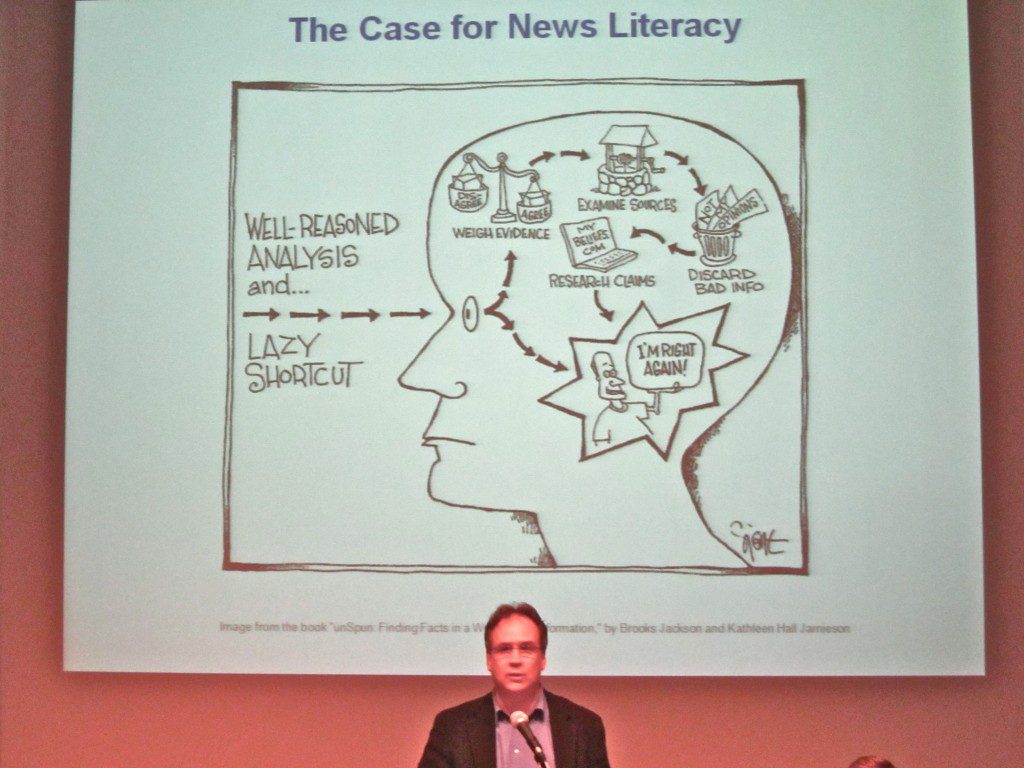

2. News Literacy Program at Stony Brook University – Fleming (2013)

Fleming (2013) provides a case study that focuses on one of the most ambitious and well-funded curricular news literacy programs. Ideologically, the News Literacy Program at Stony Brook is similar to the Powerful Voices for Kids Program, but it is an ongoing program that exclusively involves university students. Fleming describes it as an experiment in modern journalism education. This is because traditionally, journalism has had a practice-oriented philosophy, and yet as Fleming (pp. 2) explains, Stony Brook’s program ‘veered off of journalism education’s skills-development tradition and into unchartered territory called news literacy’. Howard Schneider, the founding dean of the School of Journalism at Stony Brook University, designed the program with the objective that young audiences would sharpen their critical thinking skills and come to support high-quality news. According to Fleming (2013, pp. 11), Schneider feared that important news literacy principles of the press were disappearing as the lines of “responsible” journalism and ‘everything else blurred in the fast-moving digital sea of information and disinformation’.

The approach at Stony Brook is in line with suggestions made by Mihailidis that news literacy programs should not just focus on critiquing news content but should also focus on understanding and contextualising it. According to Fleming (2013, pp. 13), this translates into an instructional strategy that teaches students how to access, evaluate, analyse, and appreciate journalism. As with the Powerful Voices for Kids Program, the success of news literacy education is largely derived from creating what Hobbs (1998, pp. 28) calls a ‘pedagogy of inquiry’, “asking critical questions about what you watch, see, and read”. The ultimate objective is to promote critical thinking skills which develop intellectual autonomy on the part of the student. The broader goal of critical thinking, according to Mihailidis (2011, pp. 4), guards against taking the mediated environment for granted. After all, as McLuhan (1969, pp. 5) pointed out, humans live in constructed media environments as unconsciously as fish live in water.

News literacy education must therefore help students understand and analyse the constructions of reality presented by journalists, which sometimes offer incomplete or inaccurate portrayals of the world we live in. This would explain the overall objectives of both the Powerful Voices for Kids Program and the news literacy course at Stony Brook, which is for students to become more consistent and sceptical news consumers, who are able to accurately assess the reliability of news. Fleming (2013, pp. 13) presents results that instructional approaches based on this approach to news literacy, include high levels of engagement, a greater awareness of current events, and deeper, more nuanced understandings of journalism.

Moreover, as alluded to by Mihailidis (2011, pp. 28), the goal of news literacy should not simply be to generate distrust or cynicism about the news, because otherwise, news literacy programs might lead to dismissive attitudes about the press and civic responsibilities in general. In one of his studies for example, Mihailidis (pp. 30) finds that a class focused on news was successful in developing critical reading and viewing skills, but it also seemed to encourage cynical views of the press. A balance needs to be struck, therefore, between teaching critical thinking skills and at the same time fostering appropriate interpretative habits about the news. It is this approach that seems to be exemplified by both the Powerful Voices for Kids Program and the Stony Brook news literacy program, which equips students to demand and appreciate quality journalism that adheres to the norms to which it aspires.

Concluding thoughts…

Aside from their effective pedagogies, the success of these two programs can be attributed to the ready availability of appropriate technologies and access to diverse news sources. These two factors facilitate the fundamental objectives of news literacy but unfortunately also represent the key challenges in the programs’ replication. Fleming (2013, pp. 14) for example, states that ‘the Stony Brook approach is not without fault because of its cost, dependence on PowerPoint presentations, and last minute updates’. Similarly, the Powerful Voices for Kids Program relies on the distribution of age-appropriate news articles, coding software (Scratch), and the support of university students. Discussing information obesity, Whitworth (2009, pp. 2) states that:

‘At the very least, we will suffer a loss in quality of engagement, and require new tools and strategies to deal with the overload’.

This same statement could apply equally well to the challenges facing news consumers. Both the Powerful Voices for Kids and Stony Brook Program have appropriate strategies in place to deal with the large quantity of news online, helping students to navigate and analyse this information. However, the replication of these strategies is limited because the tools provided on the programs themselves are costly in terms of time to prepare, organise and use. News on Atlas has been designed to reduce these costs and enable more schools to replicate the pedagogy underlying successful news literacy programmes.

References

Fleming, J. 2013. Media Literacy, News Literacy, or News Appreciation? A Case Study of the News Literacy Program at Stony Brook University. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator.

Hobbs, R. 2010. News Literacy: What Works and What Doesn’t. University of Rhode Island.

McCluhan, M and Parker, H. 1969. Counterblast.

Mihailidis, P. 2011. News Literacy. Global Perspectives for the Newsroom and Classroom.

Whitworth, A. 2009. Information Obesity. Chandos, Oxford, UK.